Understanding the eukaryotic cell cycle is pivotal for comprehending the biological underpinnings of various diseases, particularly cancer. The intricate dance of cellular processes that govern growth, replication, and eventual demise is akin to a finely tuned orchestration, where each phase plays a unique and critical role. This scientific exploration plunges into the depths of this cellular rhythm, shedding light on how deviations from the norm can lead to dire consequences, especially in the world of oncogenesis.

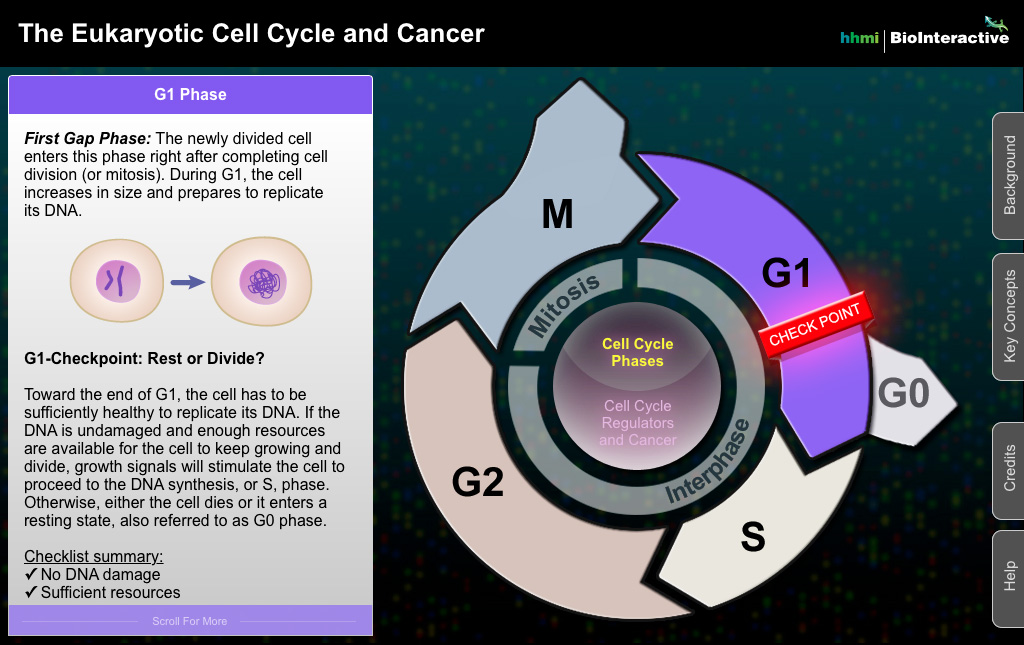

The eukaryotic cell cycle is a series of phases through which a cell progresses to duplicate itself. It comprises distinct stages, which include G1 (Gap 1), S (Synthesis), G2 (Gap 2), and M (Mitosis). Each stage of this cycle is characterized by specific cellular activities, checks, and balances that ensure fidelity in DNA replication and cell division. At its core, the cycle facilitates not just the survival and propagation of an organism, but also acts as a critical regulatory mechanism to prevent aberrant cell behavior.

To begin with, the G1 phase involves cell growth and preparation for DNA synthesis. During this phase, cells accumulate the necessary resources and nutrients required for DNA replication. This period also includes environmental sensing; the cell evaluates external factors that could influence its proliferation. Herein lies the first point of vulnerability where cellular checkpoints operate. Cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) orchestrate this regulation, ensuring that cells proceed to the next stage only when conditions are optimal. When these regulatory mechanisms falter, cellular life becomes precarious.

Proceeding into the S phase, the process of DNA replication occurs. Each chromosome is duplicated, resulting in two sister chromatids linked at a centromere. The faithfulness of this process is non-negotiable; inaccuracies can precipitate mutations that, if perpetuated, may contribute to oncogenic transformations. DNA repair mechanisms spring into action to rectify errors. However, should these repair pathways be compromised, the resultant genomic instability can set the stage for cancer development. Here, the role of tumor suppressor genes, such as p53, becomes exceedingly crucial; they act like custodians, defending the cell against malignant transformation.

The G2 phase acts as a final checkpoint before mitosis. At this juncture, the cell ensures that DNA replication has been completed without errors. Any damage detected must be repaired before the cell divides. The precision of this check is paramount. Failure to rectify such damages can allow cells to enter mitosis with deleterious genetic alterations. This phase is heavily regulated and closely monitored, as the integrity of the entire organism hinges on this momentous decision.

Mitosis, the M phase, is when the cell’s duplicated chromosomes are segregated into two daughter cells. This procession is meticulously choreographed into phases (prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase) that guarantee the accurate distribution of genetic material. Any misstep here — a phenomenon termed aneuploidy — may foster a fertile ground for cancer. Such recent discoveries elucidate the complexities of how cellular misbehavior can burgeon into oncological disease.

Delving deeper into cancer’s etiology, it becomes clear that mutations can arise from various external factors — environmental carcinogens, radiation, and even lifestyle choices. However, what is particularly alarming is the role of inherited genetic predisposition. Individuals bearing mutations in proto-oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes find themselves at a significantly heightened risk for cancer. Here lies the intersection of genetics and the cell cycle; the predisposition often exacerbates the occurrence of dysregulation within the cell cycle machinery, leading to the insatiable cellular proliferation characteristics of cancer.

Moreover, recent studies reveal that the tumor microenvironment can also significantly influence cancer progression. Signals from surrounding tissues can either stymie or accelerate abnormal growth. This interactive paradigm underscores the necessity for a holistic approach to cancer treatment, including not just targeting the tumor cells but also modulating the microenvironment to restore normalcy.

Beyond the cellular implications, the psychological and emotional dimensions surrounding cancer cannot be overlooked. A cancer diagnosis profoundly impacts an individual’s mental health, often resulting in anxiety and depression. The mood-boosting experiences that come from addressing these psychological aspects can significantly enhance the quality of life for patients. Thus, understanding the cell cycle and its implications for cancer simultaneously paves the way for therapeutic avenues that encompass not just physical treatment, but also psychological support.

In conclusion, the eukaryotic cell cycle is an extraordinary illustration of biological precision. Its regulation is a testament to the fine line between health and disease. Capitalizing on this understanding offers tremendous opportunities not just for targeting cancerous cells directly, but also for harnessing preventative strategies that could one day mitigate the looming threat of oncogenesis. As research progresses, the promise of better diagnostic tools and treatments continues to unfold — a chronicle of hope amidst the complexities of life at the cellular level.